My most recent read took me much longer to get through than I would have liked, but it was well worth it. The Age of Wonder by Richard Holmes is a history of science through the Romantic Era (1780

s-1830s) told through English science. Possibly the best nonfiction I've read in some time, Holmes himself appears to be more of an historian of romanticist literature and history, and in the undying words of my brother-in-law, an "englishist." What sets this apart from many of the other scientific histories I've read is Holmes' sense of literature and poetry itself. The story-telling like style (focusing primarily on three figures in English science, Joseph Banks, William Herschel, and Humphrey Davy) does a wonderful job of telling the interconnectedness of science, philosophy, literature, politics, and society readily apparent in 18th century society as it is today. Indeed, it was not uncommon for the likes of the young Michael Faraday or Caroline Herschel to have had dinner parties and correspondence with the literary and philosophical luminaries such as Coleridge, Keats, Wordsworth, the Shelleys, Lord Byron, and Kant.

s-1830s) told through English science. Possibly the best nonfiction I've read in some time, Holmes himself appears to be more of an historian of romanticist literature and history, and in the undying words of my brother-in-law, an "englishist." What sets this apart from many of the other scientific histories I've read is Holmes' sense of literature and poetry itself. The story-telling like style (focusing primarily on three figures in English science, Joseph Banks, William Herschel, and Humphrey Davy) does a wonderful job of telling the interconnectedness of science, philosophy, literature, politics, and society readily apparent in 18th century society as it is today. Indeed, it was not uncommon for the likes of the young Michael Faraday or Caroline Herschel to have had dinner parties and correspondence with the literary and philosophical luminaries such as Coleridge, Keats, Wordsworth, the Shelleys, Lord Byron, and Kant.Personally, I have always had an affection for romanticist works, in its epic grasp of all love, hope, power, beauty, misery and trembling universality. What really pulled this book together was the recognition that science and poetry themselves are in fact two sides of the same coin: in searching for the innate beauty of the world. The story of tropic, polar, aerial, electric, and chemical exploration in as the eighteenth century passed into the nineteenth has a true sense of its place in history as well. Politically, the romanticists saw the mental decline of George III, the loss of the American colonies, Napoleon's rise, fall and rise again, the establishment of the Regency, and eventually the passage into the Victorian era with her coronation in 1837. Moreover, as so many places in history show, a time of philosophical transition (called "paradigm shifts" by Thomas Kuhn) is truly fascinating... in the early Industrial Era, Britain and Europe as a whole was beginning to shake off the last of the medieval hangers-on. Much of science in the early modern era (16th-early 18th c.) was closely tied to philosophy and religion of the time. Many men of science were deeply pious (such as Newton, Kepler, Galileo), and spoke freely of God in their writings; however, their view of the cosmos, as soon through the lens of the natural world led to the rise of Deist philosophies in the 1700s. By the end of the 1800s, "natural philosophy" which often speculated on the nature of Creation and of Man as well as its subject manner evolved into the science we know today, objectively of its own philosophies.

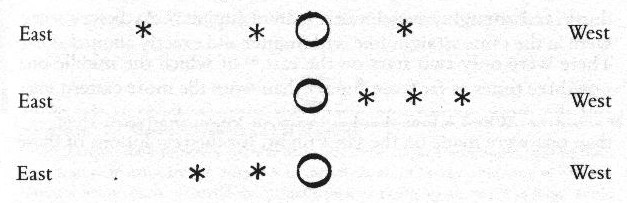

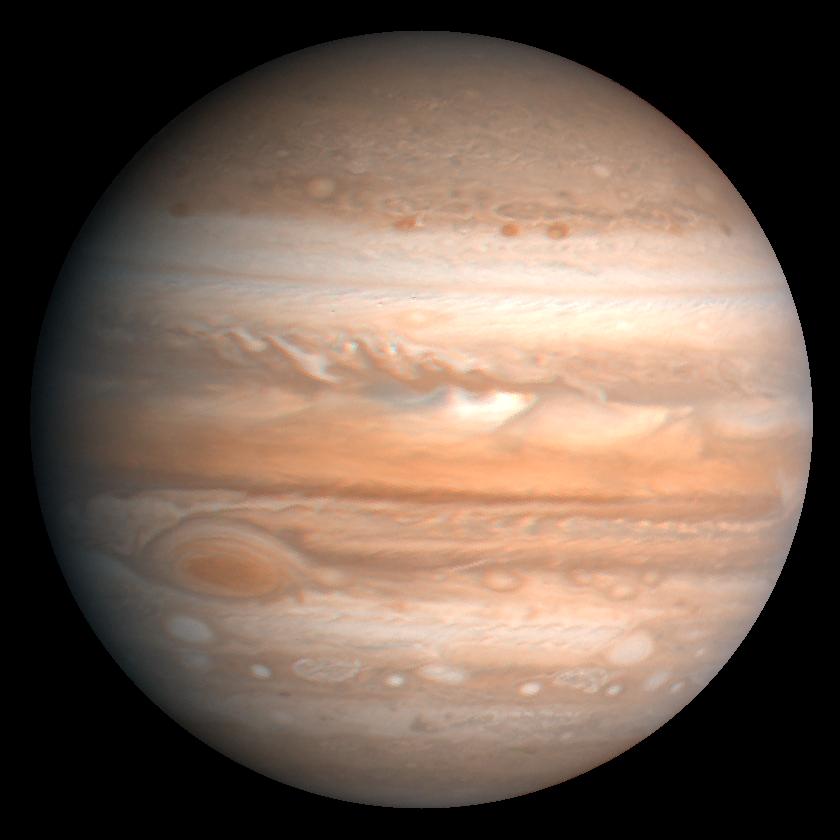

Many interpreters of Romantic poetry cite Coleridge and Keats as decrying science as robbing nature of is mystery and beauty. Holmes, however, attacks this interpretation, showing how in literature itself of the era, scientists are to be highly praised and loved as those who can truly see the magnificent, beautiful, unity of the Universe. Seen through the awe-inspiring knowledge when Herschel announced an infinite Universe with worlds beyond our imagination. It was seen in Davy's initial exploration into gases and human consciousness itself. This was seen when French ballooneers first saw the world from on top.... when looking down, human borders and faults melted away into the beauty of a landscape from miles up.

I've been making mental notes for myself to get poetry books off of the shelf now that I've read this. It is always an amazing reminder to see the world itself as a living poem