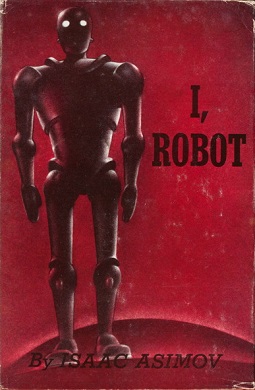

I, Robot by Isaac Asimov

To begin with, while there are many editions of many books out there, the cover art that normally goes up with these reviews is that of the edition which I read. The physical book beside me right now is the 2004 printing, which my brother loaned to me (thanks Will!). Unfortunately, this was the same year in which a film of the same title, that had little to do with the novel, premiered. As I was holding a cheap paperback in which Will Smith glared at me with a vaguely futuristic and ominous, if worried countenance.

{damnit, Will Smith, cut that out}

Firstly, just about anyone who has read Asimov places him as the father of modern science fiction, and from what I have read of his early work (Foundation trilogy, "Nightfall"), I can agree an overflowing imagination and use of fundamental science are the principles of his work are highlights of Asimovian sci-fi.

More than anything else, Asimov constructs an entire universe around his fiction, in which he employs a similar method as Foundation, as telling his narrative through a series of thematically-related, chronological short stories. The novel itself takes the form of a 2064 interview of the elderly Dr. Susan Calvin, a roboticist who shepherded the dawn of the robotic age. Dr. Calvin's second- and first-hand recollections of twenty-first century history from the simple robotics in the 1990s to the global-scale positronic brains of the 2060s is a series of accounts in which the human creators struggle with, understand, and learn about their own creations through the regular, logical actions of the machines.

Dr. Calvin herself is always described in the text as cold and emotionless, moreso than even her robotic subjects. The ever-logical and steadfast nature of this personality characterizes the book. Central to any of Asimov's description of robotkind are the Three Laws of Robotics:

- A robot may not harm a human being, or through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm

- A robot must obey any orders given by a human being, unless such orders conflict with the First Law

- A robot must protect its own existence, unless doing so conflicts with the First or Second Law

The concept of robopsychology as Calvin's field of study seems a bit abstract to me. As the entirety of robot's "personalities" are dictated by the Three Laws (and occasionally hints of the zeroth), one would think that any personality the robot would have would be rather straightforward and predictable, but then again, most of the stories in I, Robot are peculiar cases where behavior is unexplained. Or, I could study a bit more about artificial intelligence, even though it's always made me a bit paranoid. While Asimov's ideals about the Laws dictating all robotic behavior are wonderful (especially the bit about the positronic brain melting before harming a person), I feel that the real history of AI tilts to a more pragmatic robot which gets the job done, as programmed by its creators. Let's not forget that we do live in the future, after all.

The author should not be begrudged praise... this is a finely written book, with an excellent imagination for the era (1950), and if anything, I'm a bit disappointed that robots are not as benign and just as Asimov had hoped. At parts it is a dry read when compared to his more colorful work; but in truth, Asimov was a scientist by training, who saw the world as thoroughly organized and beautiful; while is work wonderfully operates within the laws of nature, I feel he greatly restrained endless possibilities of development by restricting the story to additionally operate within the laws of robotics.

Both the central character's and author's endless reverence for the positronic brain is appreciated, but as it is seen to some degree with Dr. Asmiov and to an almost misanthropic degree with Dr. Calvin, there was an overarching theme that the innate "goodness" of robots was always greater and more concrete than the goodness, abilities and creativity of mankind. Sure, the robots are infinitely rational and selfless and obedient, but don't count humans out of the game just yet. In the constructed 21st century of the novel, I'm probably one of the cranky old Fundamentalists who don't trust the mechanical men. I'm okay with that though (I'm going to be one of those awesome old guys who's always ranting about something and shaking a cane.... kids of the 2050s, watch out).

In fact, the developing field of artificial intelligence in all likelihood places what will be the real world's equivalent of the positronic brain in an interactive console that a move-around humanoid machine. Although no futurist (ask Ray Kurzweil for more details), the next decade or two will be staggerinly fascinating when a synthetic mind can consider us as we consider it. A field developing faster than the common press can keep up, this brings so much of what "science fiction" is to our daily lives. As usual, the only thing more fascinating than the dreams of fiction writers is when these are written by history.

To finish off, let's hope that these Three Laws do get programmed into our future mechanical overlords, and that we remind them that we are a good, benevolent race of squishy irrationals.